ArXiving on March 2018

Let us celebrate this new Spring with some papers fetched from arXiv, not necessarily from the last weeks but at least in reverse chronological order in my Twitter timeline.

Crisan, A., Munzner, T., & Gardy, J. L. (2018). Adjutant: an R-based tool to support topic discovery for systematic and literature review

A short paper describing a Shiny application allowing to fetch data from Pubmed and to apply topic clustering on the results using t-SNE followed by the hdbscan (R package) algorithm. Importantly, data can be saved locally if the user want to perform additional analyses.

Nuijten, M. B., Van Assen, M. A. L. M., Augusteijn, H. E. M., Crompvoets, E. A. V., & Wicherts, J. M. (2018). Effect sizes, power, and biases in intelligence research: a meta-meta-analysis

Michèle B. Nuijten is the co-author of the statcheck R package, which offers to verify p-values reported in scientific articles. It was created to help assist in meta-analyzing a bunch of papers in the psychological litterature; see Nuijten, M. B., Hartgerink, C. H. J., van Assen, M. A. L. M., Epskamp, S., & Wicherts, J. M. (2016). The prevalence of statistical reporting errors in psychology (1985-2013). Behavior Research Methods, 48(4), 1205-1226.

In the present paper, the authors assessed effect size and power reported in 131 meta-analyses in intelligence research. As expected from this type of research field where psychometric scales are used, Pearson’s correlation was often used to report effect size (42 studies) even if it might be wiser to use disattenuated correlation measure as recommended in the psychometric literature, or Cohen’s $d$ (for comparison of pairs of means). All effet size measures were expressed as Pearson’s $r$. The results can be checked online. Correlations were found to be on average around 0.25, with an achieved statistical power just below 50% (only one third of all 2,439 primary studies reach the 80% power threshold) with worser results in behavorial genetics studies .

Lehman, J., Clune, J., Misevic, D., Adami, C., Beaulieu, J., Bentley, P. J., Bernard, S., … (2018). The surprising creativity of digital evolution: a collection of anecdotes from the evolutionary computation and artificial life research communities

This is a big discussion of evolutionary algorithms which reminds me of The Nature of Code, by Daniel Shiffman (available on GitHub as well). I enjoyed reading his book two years ago, and now I am watching Daniel Shiffman on the coding train on Youtube from time to time.

The process of evolution is an algorithmic process that transcends the substrate in which it occurs.

In the present review, the authors discuss several lessons learned from bugs or failed attempts at demonstrating an expected outcome in scientific studies and which turned to bring interesting new ideas. They are presented as sort of “greatest hits” collection of anecdotes, according to the authors. For instance, here is an example that people involved in randomized clinical trials would love: In an experiment involving reinforcement learning using neural networks, the authors forgot to randomize the order of the stimuli such that in the end the neural network just learned to exploit the regularity of the pattern rather than to tune its connections to the edibility of each item.

Mehta, P., Bukov, M., Wang, C., Day, A. G. R., Richardson, C., Fisher, C. K., & Schwab, D. J. (2018). A high-bias, low-variance introduction to machine learning for physicists.

Sometimes you come across some big work on arXiv. This is it! Here is a fresh new introduction to Machine Learning techniques, in a hundred of pages, for physicists this time. The companion website has everything to get started with iPython notebooks and the scikit-learn library. The applications cover basic algorithms like gradient descent and popular statistical methods: (regularized) linear and logistic regression, bagging and boosting, deep neural network using Keras, TensorFlow or PyTorch, and even variational auto encoders using Keras. I should note that the authors introduce ML as a subfield of AI without further ado (why is this is not considered as a subfield of statistics?) and that they “focus on prediction problems and refer the reader to one of many excellent textbooks on classical statistics for more information on estimation” (other than prediction, I have a hard time believing that black-box models like bagging and boosting can offer anymore than predictive performance over well tuned regression models).

Drovandi, C. C., Grazian, C., Mengersen, K., & Robert, C. (2018). [Approximating the likelihood in approximate bayesian computation](Approximating the likelihood in approximate bayesian computation)

This paper presents alternative approaches to approximate bayesian computation (ABC) which allows to compute a non-parametric estimate of the likelihood of a summary statistic based on computer simulation. This covers a bayesian version of the synthetic likelihood method proposed by Wood (2010) and the non-parametric empirical likelihood developed by Mengersen et al. (2013) The latter allows for the use of Bayes factor in model comparison and it also avoid computational simulation under certain circonstances.

Morris, T. P., White, I. R., & Crowther, M. J. (2017). Using simulation studies to evaluate statistical methods

This is a nice review of computational approaches to statistical inference with an emphasis on providing guidance for newcomers and experienced practitioners in biomedical research. Key concepts are detailed in the article but here are the main steps: planning and aims of the simulation study, methods, target of analysis, performance measures, coding, analysis, reporting. Regarding performance measures, it is interesting to note that among 100 papers published in Statistics in Medicine, bias and coverage of $(1-\alpha)$ confidence intervals were the most frequently indicators studied by the authors, while type I error rate was only assessed in one-third of the studies. A working example based on the proportional hazards model (§7) is used to illustrate the various steps of a simulation study.

McShane, B. B., Gal, D., Gelman, A., Robert, C., & Tackett, J. L. (2017). Abandon Statistical Significance

If you did not follow the buzz around statistical significance and p-value, here is a short paper for you.

(T)he status quo is that p < 0.05 is deemed as strong evidence in favor of a scientific theory and is required not only for a result to be published but even for it to be taken seriously.

Kim, Y., & Li, J. (2018). Serverless data analytics with flint

Flint depends on AWS (S3 bucket) and Lambda. It allows you to use Spark without having to worry about installing Spark on your local machine, while Flintrock is a command-line utility that allows to launch and manage a cluster on EC2.

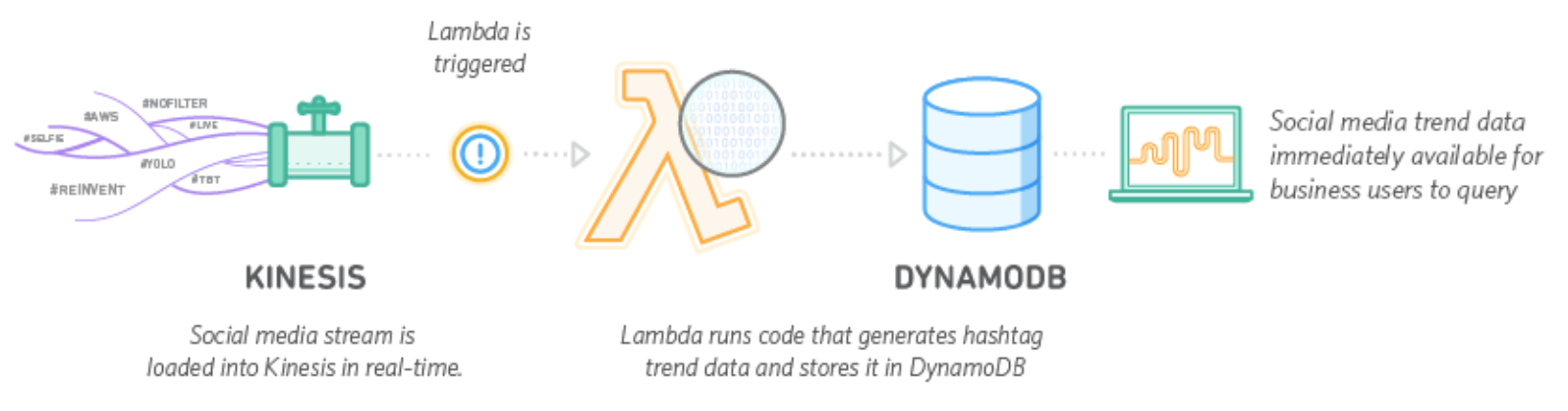

AWS Lambda is one of the next-generation service from Amazon. It let you run any code in a serverless environment according to a pay-as-you-go cost model: Amazon takes care of allocating ressources and managing parallel execution of your code. Moreover the execution can be triggered by external event, like in Travis CI. As an example, consider an image processing pipeline where each time an user upload an image on an S3 bucket, a Lambda to generate an image thumbnail is triggered. For a standalone application, take a look at Seth Brown BeerAI recommender system.

Aaronson, S. (2011). Why Philosophers Should Care About Computational Complexity

Still on my reading list.

Bacry, E., Bompaire, M., Gaïffas, Stéphane, & Poulsen, S. (2018). Tick: a python library for statistical learning, with a particular emphasis on time-dependent modelling

Tick is a new Python package for Machine Learning of time-dependent events, including Hawkes processes (I know nothing about those processes but I like the name : smile :; for more details, see this review). It also features penalized linear and logistic regression and the paper includes a small benchmark of those models against their scikit-learn counterparts.

♪ Leonard Cohen • Popular Problems