ArXiving on March 2020

Here are some papers that I read this week.

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect arXiv:2003.11635v1

This is a fair review of the Book of Why that I started reading a while back before forgetting about it because I’m no longer involved in causal analysis, and not curious enough to keep up with everything that’s going on around here. Anyway, graphical causal representation under the umbrella of direct acyclic graphs (DAGs) are supposed to be the new starting point for causal analysis. The reviewers remain, however, critical of the Judea Pearl’s optimism since his approach mostly relies on the assumption that the underlying causal structure is known.

We believe this optimism is unfounded. The central problem that scientists face, especially in the social sciences, is not how to express or analyze causal models but how to pick one that is valid or at least reasonable. The book does not claim to solve this problem.

I would say that the same criticism applies to all regression models insofar as the (frequentist) interpretation value is valid (and meaningful) conditional on the fact that the model is correctly specified. Another criticism, this time, aimed at denigrating the usefulness of the experimental approach, like randomized clinical trials or experimental design at large. Finally, DAGs are not the only appraoch to causal modeling, according to this review, for several alternative causal models, like nonparametric structural equation models or design-based approaches, exist and may be able to answer the specifics of causal discovery.

An Introduction to Probabilistic Programming arXiv:1809.10756

I’ve read several papers or arXiv reviews on probabilistic programming (PP) lately. I mentioned this one already. Briefly, it provides an extensive review of the core ideas of PP, namely the importance of conditioning in probabilistic machine learing and the use of dynamic computation graphs. Interestingly, this uses the Clojure dialect as the main implementation. This should come as no surprise since some of the authors are actively involved in the Anglican toolbox.

Related threads: A tour of probabilistic programming language APIs, Probabilistic programming with Monad-Bayes.

A Survey of Deep Learning for Scientific Discovery arXiv:2003.11755v1

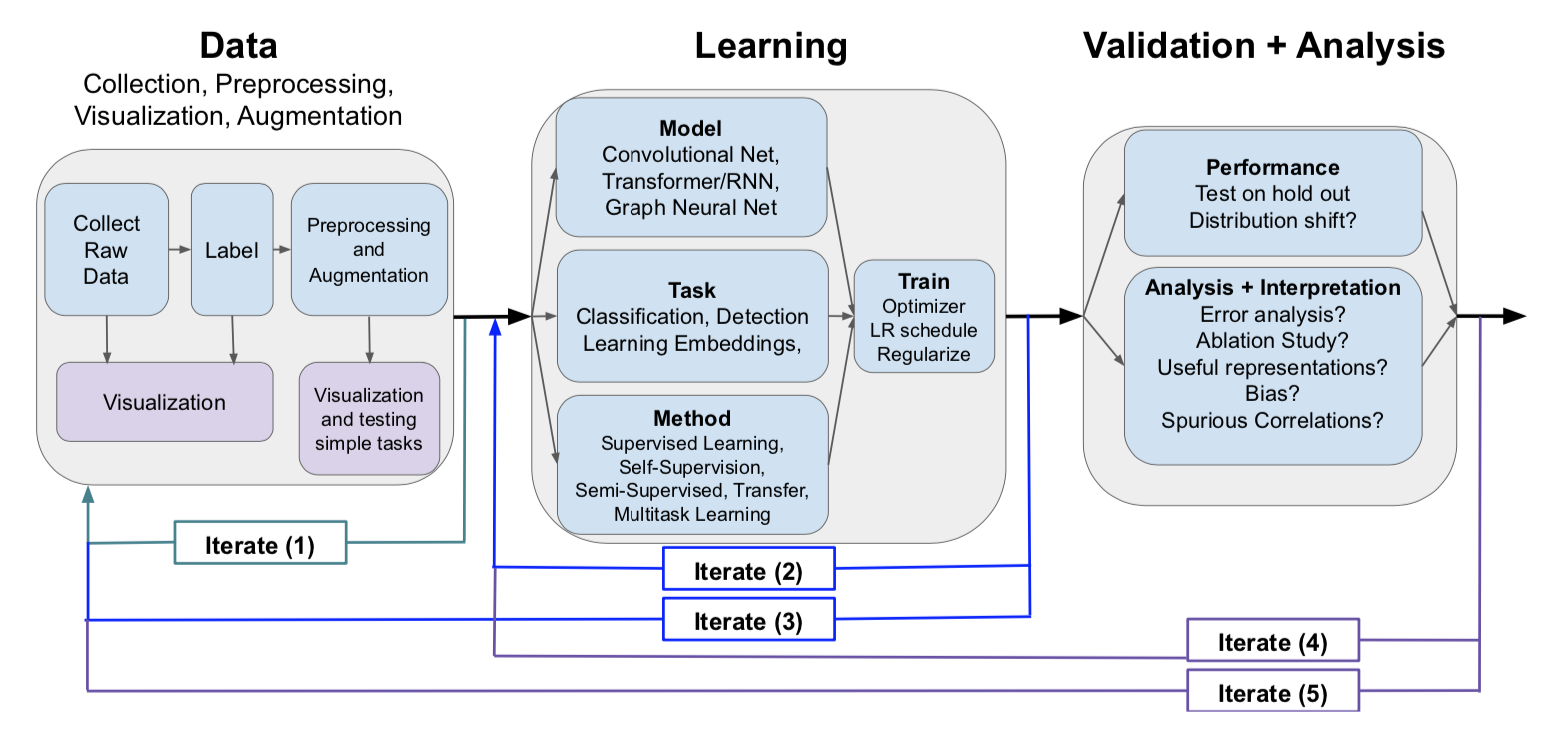

This review is structured along two ideas: to provide an overview of many widely used deep learning models, spanning visual (CNNs), sequential (RNNs) and graph structured data, associated tasks (image segmentation, super-resolution, sequence to sequence mappings and many others) and different training methods, and to highlight techniques that use deep learning (DL) with less data (e.g., self-supervision or semi-supervised learning) and better interpret these complex models. In my own view, DL is a useful technique when some kind of regularities can be exploited in the data — including bias if any, and when the training size is large. This generally holds in the case of pattern recognition tasks like NLP or image processing, but I remain sceptical about the application of this type of model in tasks for which more traditional supervised methods (e.g., logistic regression) would be just as suitable. There are also lot of links regarding tutorials and software, that are not necessarily limited to DL.

Reinforcement Learning in Economics and Finance arXiv:2003.10014v1

I have no competency in finance, and I barely have notions in economics, but I always enjoy reading one of Arthur Charpentier’s review, for they are always very picky and highly anchored in historical considerations. The last one I read was about Machine Learning, and it was really englightening. I am in the middle of the present review, and I already learned a lot on the parallel between traditional ML and RL with respect to loss (regret) minimizaetion, bandits, dynamic programming, or even Thompson sampling strategy.