lost+found 2018

After excavating unifinished or rough draft posts from last year (a quick ack "draft\s?[:=] true" content/post/*.md in the Hugo directory), we should now be ready for June.

2018-04-21

This post could have been headed “In which we learn how to embrace functional programing for statistical computing”, or “how I stoped worrying about R and look for more lispy paradigm for data science.” but let keep it simple for a while. Lately, I was looking for a nice way to perform numerical simulation in Clojure, I mean other than using lazy sequences with (take 10 (repeatedly #(rand-int 10))) where you can hardly fix any seed that will help reproduce your random numbers. I am aware of Clojure data.generators but I wanted a more integrated framework. Here are some extra libraries for numerical or statistical computing with Clojure that I found while crawling the web.

I heard about Cortex by reading Carin Meier’s blog post some time ago.

Regarding Probabilistic Programming, you will find interesting discussion of Bayesian inference in this recent PhD thesis: Probabilistic Programming: Automation of Inferences, Learning and Design (PDF)

It is quite easy to find good (non-cryptographic) PRNGs written in Clojure. You will likely came across one from L’Ecuyer and coll. or the Mersenne Twister algorithm, for instance. However, following John D Cook suggestion, you can also easily write your own code, based on existing algorithm.

2018-04-23

This time, I am (quickly) reviewing Think Bayes, one of Allen Downey’s book from the “Think X” series. A PDF version is available on Green Tea Press. The accompanying code can be downloaded from Github (ThinkBayes is for Python 2, ThinkBayes2 targets Python 3 but the book has not yet been updated to reflect the changes).

I first read How to think like a computer scientist (probably the Python version) back in the 2000s. I really liked Allen’s approach to exposing soft and hard concepts related to computer science. This time, the author choose to use Python and discrete mathematics to expose the reader to Bayesian statistics:

Most books on Bayesian statistics use mathematical notation and present ideas in terms of mathematical concepts like calculus. This book uses Python code instead of math, and discrete approximations instead of continuous mathematics. As a result, what would be an integral in a math book becomes a summation, and most operations on probability distributions are simple loops.

But note that even if the author offers to tackle such problems from the perspective of computer science, statistical considerations remain an important part of the process, even if this yields “an approximate solution to a good model”:1

I think it is important to include modeling as an explicit part of problem solving because it reminds us to think about modeling errors (that is, errors due to simplifications and assumptions of the model).

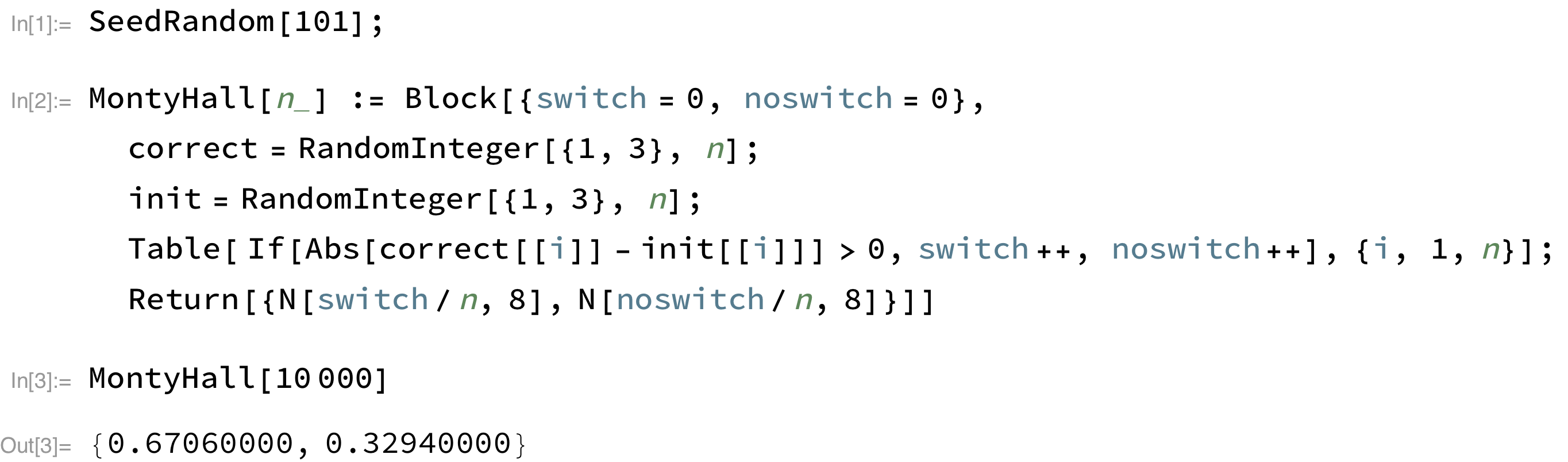

Chapter 1 provides a quick exposition to Bayes theorem, described as a way to get from P(B|A) to P(A|B), especially in cases where P(A|B) is not easy to compute. I find that the M&M problem (§1.6) is a very nice way to introduce bayesian inference, in the spirit of Philip Good’s introduction to permutation testing (Permutation, Parametric, and Bootstrap Tests of Hypotheses, Springer, 2005): define the problem, set up the hypotheses and a test statistic, and finally assess the likelihood of the observed result; or, as the author suggests in Chapter 3: (1) choose a representation for the hypotheses, (2) choose a representation for the data, and (3) write the likelihood function. The next one is about the Monty Hall dilemma and it is really trickier.2 It is, however, easy to run a little simulation of the expected proportion of wins in case we choose to switch or stick to our initial choice. Here are the results I get using Mathematica:

Of note, a collection of related problems (with solutions) can be found on the author’s blog: All your Bayes are belong to us!.

In Chapter 2, the author provides reminders about the basics of probability distributions in Python (using a custom Python module, thinkbayes.py, that can be found on the Github repository), followed by two numerical applications on the aforementioned problems. It is mostly Python code drawing from the so-called template method pattern.

Chapters 3 and 4 are all about estimating (…)

2018-10-27

Here is a little excursion into algorithms for cycle detection, with a particular emphasis on palindrome.

The following comes from Programming Praxis, which I happen to read from time to time:

Write a program that determines if a linked list of integers is palindromic — i.e., reads the same in both directions. Your solution must operate in O(1) space.

In the suggested solution, the author uses Floyd’s tortoise-and-hare algorithm, also known as Floyd’s cycle-finding algorithm, whose name is mentioned in Don Knuth’s TAOCP (Seminumerical Algorithms) although it is not .3

2018-10-29

The rectangles algorithm is used to generate random variates based on the acceptance–rejection method. Here is a small implementation using Clojure.

The article is available online, but in a few words the idea of this algorithm

Recall that the PDF for a gaussian random variable (r.v.) is

$$ f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}}\exp\left(\frac{-(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right), $$

for $-\infty < x < \infty$, where $\mu$ and $\sigma^2$ denote the mean and variance of the distribution. In general, it is easier to consider a standard normal deviate $Z$, with $\mu=0$ and $\sigma=1$, since we can always use the transformation $X = \mu + \sigma Z$.

Reference: Zhang, R., & Leemis, L. M. (2012). Rectangles algorithm for generating normal variates. Naval Research Logistics, 59(1), 1–6.

2018-11-22

Most of what is available in terms of tutorial or solution to problems from programming contests, also called competitive programming, relies on C or C++–see, e.g., this earlier post of mine on the Competitive Programmer’s Handbook. I recently came across this Bachelor’s thesis (PDF, 44 pp.) where the author offers solutions to various problems in C++. Here I will try to offer some Scheme or Lisp solutions (one at a time). Today, we shall start with the well-known Knuth-Morris-Pratt (KMP for short) algorithm which is widely used for pattern matching, usually on strings. This algorithm is linear in time and has asymptotic complexity $\mathcal{O}(n)$. To understand what the difference between the KMP and the Boyer-Moore’s algorithm are, see this related Stack Overflow thread.

The proposed task reads as follows:

Given an integer N, make a palidrome (word that reads the same when you reverse it) of length at least N.

First, we need a working version of the KMP algorithm and I will use Racket Scheme. Note that the documentation on string libraries (SRFI 13, R5RS) discusses the KMP algorithm.

http://www-igm.univ-mlv.fr/~lecroq/string/node8.html http://www.inf.fh-flensburg.de/lang/algorithmen/pattern/kmpen.htm

Here is one solution in Scheme from codecodex:

(define (init-next p)

(let* ((m (string-length p))

(next (make-vector m 0)))

(let loop ((i 1) (j 0))

(cond ((>= i (- m 1))

next)

((char=? (string-ref p i) (string-ref p j))

(let ((i (+ i 1))

(j (+ j 1)))

(vector-set! next i j)

(loop i j)))

((= j 0)

(let ((i (+ i 1)))

(vector-set! next i 0)

(loop i j)))

(else

(loop i (vector-ref next j)))))))

(define (kmp p s)

(let ((next (init-next p))

(m (string-length p))

(n (string-length s)))

(let loop ((i 0) (j 0))

(cond ((or (>= j m) (>= i n))

(- i m))

((char=? (string-ref s i) (string-ref p j))

(loop (+ i 1) (+ j 1)))

((= j 0)

(loop (+ i 1) j))

(else

(loop i (vector-ref next j)))))))

2019-01-10

Here is a little programming entertainment in Racket to console me for wasting two hours fighting with Excel.

Briefly, I spent nearly two hours figuring out how to perform a simple regression analysis and some trivial parametric statistics using Excel for a colleague of mine. I don’t even talk about computing Spearman rank correlation when there are ties and you must manually apply a correction because there is no automated function in vanilla Excel for that. After I transmitted the result of my morning work, I thought it would finally go as fast to implement a gradient descent algorithm in Scheme and use Gnuplot or anything else for data visualization. Atabey Kaygun already did this using Common Lisp, but Racket should do the job as well, notwithstanding the fact that we can benefit from a lot of built-in packages.

First, we need a CSV reader because the dataset is available as a comma-delimited text file. We will also need basic helper functions to summarize the data, and also a plotting framework to visualize the data. Finally, the gradient descent algorithm itself, which consists in starting with an initial set of parameter values for a given function and iteratively moving toward the set of parameter values that minimize the function. Iteration translates easily in Lisp recursion. In our case, the parameters correspond to the intercept and the slope of the regression line. Obviously, we need an objective or cost function to evaluate and it is based on the squared distance measure of observed and fitted points, much like how residuals are defined in the standard OLS approach. The term “gradient” comes from the fact that we will be working with partial derivatives of the estimated parameters.

Gradient descent is probably best known in Machine Learning applications since more classical and closed-formed algorithms are used to solve OLS problems. Depending on the data structure, however, the GD algorithm might provide an interesting alternative, especially in the case where $n$ is large, and it works in the case the response variable is binary (aka logistic regression). Note also that there are also other well known variants of this algorithm, like batch or stochastic gradient descent.

Here is the final code: (also available to download)

Note that you must install csv-reading first, e.g., using raco pkg install csv-reading at the prompt of your preferred shell.

2019-01-16

Today we are going to build a correlation heatmap using a few Stata commands.

Note that there already are some solutions available on the Stata FAQ from the UCLA website. However, it relies on contour or scatter plot while we want to display something more akin to a heatmap with filled cells rather than symbols or contour lines. See, e.g., Nathan Yau’s description of a heatmap.

A quick search on the internet suggest that it is possible to use hmap or plotmatrix, and I even learnt about transition probability color plots (PDF) even it is barely related to our subject. Other interesting ideas were once discussed on Stata List.

This reminds me of John Tukey’s famous quote: “Far better an approximate answer to the right question, which is often vague, than an exact answer to the wrong question, which can always be made precise.” (The future of data analysis, Ann Math Statist 1962, 33(1): 1–67) ↩︎

It seems that unlike humans birds might be able to adapt their behavior in order to maximise their expected winnings (Are birds smarter than mathematicians? Pigeons (Columba livia) perform optimally on a version of the Monty Hall Dilemma, J Comp Psychol 2010, 124(1): 1-13) ↩︎

Exercice 6 from DEK reads as follows (with minor edits): Suppose that we want to generate a sequence of integers $X_0, X_1, X_2, \dots$, in the range $0 \leq X_n < m$. Let $f(x)$ be any function such that $0 \leq x < m$ implies $0 \leq f(x) < m$. Consider a sequence formed by the rule $X_{n+1} = f(X_n)$. Show that there exists an $n > 0$ such that $X_n = X_{2n}$; and the smallest such value of $n$ lies in the range $\mu \leq n \leq \mu + \lambda$. Furthermore the value of $X_n$ is unique in the sense that if $X_n = X_{2n}$ and $X_r = X_{2r}$, then $X_r = X_n$. ↩︎