Book review: Mathematica (2)

As a sequel of this previous post, here are two other books on Mathematica that I read this year.

An Engineer’s Guide to Mathematica (Magrad, 2014)

This book is organized in two independent parts. Part 1 summarizes Mathematica syntax. It covers basic math expressions, but also strings and quantities, which were introduced as Quantity in Mathematica 9. The author then describes how to manipulate lists and arrays, and how to define pure functions or custom modules. Symbolic and numerical mathematical applications are discussed in chapters 4 and 5, while the last two chapters deal with static and interactive graphics.

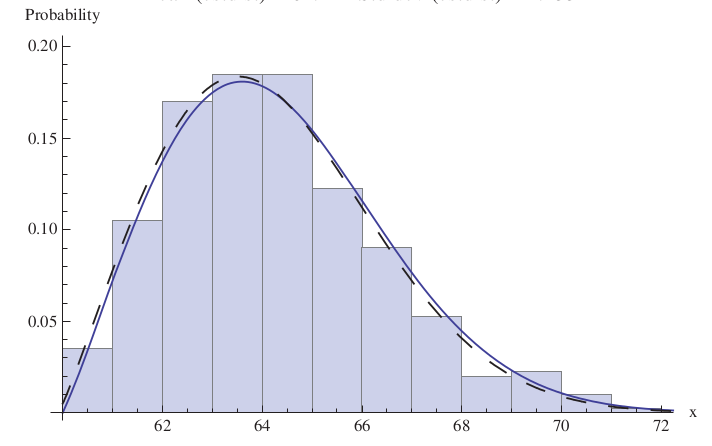

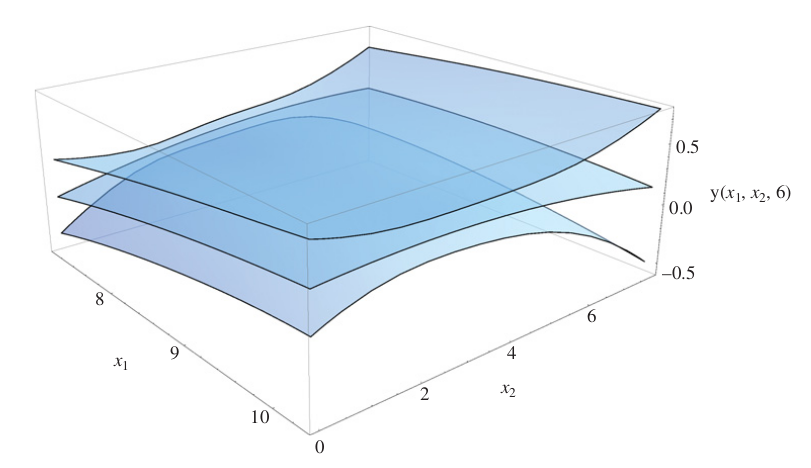

Part 2 is about engineering applications, but I was only interested in chapter 9 which deals with statistics, specifically probability distribution – and to estimate best-fitting distribution parameters, and linear and non-linear regression. Surprisingly, there’s even a section on factorial ANOVA

Except for the first chapters, explanations are rather scarce and the author usually just shows sample instructions. It’s up to you to adapt the commands and options to your own problem. Good thing is that the author provides many summary tables of commands and/or options. Also, several exercises are proposed at the end of each chapter, which I find a great way to practice all the packed information. Solutions are available on request.

Essentials of Programming in Mathematica (Wellin, 2016)

This book also features introductory chapters which I found more interesting since the author explains the how and why of each command. This is quite normal after all since the emphasis of this book is on programming rather than using dedicated functions for specific applications. I said this book is full of explanation and it also applies to small programs developed along the way, e.g., the sieve of Eratosthenes in chapter 6.

Once your code is written, your job as a programmer is not done. You must test your code under both “regular” and “abnormal” conditions, that is, using what you think is typical input and also testing the code when given pathological or atypical input. You should include tests for correctness and efficiency.

The chapter on visualization is also quite interesting since it describes some not so usual displays (dot plots, path plots). The last two chapters are especially useful if you’re a serious Mathematica developer, which I’m certainly not, and I found it particularly interesting as a complement to this already brilliant list of Mathematica resources. At the moment, this is certainly the book I would recommend to learn the intrinsics of Mathematica and to develop efficiently with Mathematica notebooks (there’s no mention of Wolframscript).

♪ The Jesus and Mary Chain • Down On Me