The Mature Optimization Handbook

Yesterday day read was about “optimization”, namely the Mature Optimization Handbook written by Carlos Bueno. See also this HN thread.

I should note that the book is nicely typesetted and can be viewed in full-screen mode on a Mac—I really like this since it is often hard to read a PDF book using two-page layout on a 12 inch monitor with default font setting (usually, 8 to 13 pt).

I really like the opening quote from Don Knuth (in Structured programming with go to statements), probably well known from experienced programmers:

Programmers waste enormous amounts of time thinking about, or worrying about, the speed of non- critical parts of their programs, and these attempts at efficiency actually have a strong negative impact when debugging and maintenance are considered. We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time; premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our op- portunities in that critical 3%.

The idea that over-optimizing (e.g., to speed up a program or decrease memory consumption) is not always worth is at the heart of this book, and the solution proposed by the author is to always measure it. This is a hard task because performance is not only related to the code itself, but it also depends on the programming language, the compiler that implements this language (we will assume that this is compiled or transpiled code), the software and the hardware stuff, and so on. So that Big-O complexity of a given program is not the only one usual suspect, and we need to account for many other “environmental” factors (hardware, CPU, GPU, etc.). This is somewhat akin to full reproducibility in computational science and how we define what a negligible difference between two results is. And this all assumes that we are measuring the right thing, and correctly (see chapter 7). The author provides some counter-example in Chapter 3: Facebook team was trying to optimize a virtual machine for PHP by finding and optimizing functions that consumed the most CPU time, but they ran into CPU caching issues.

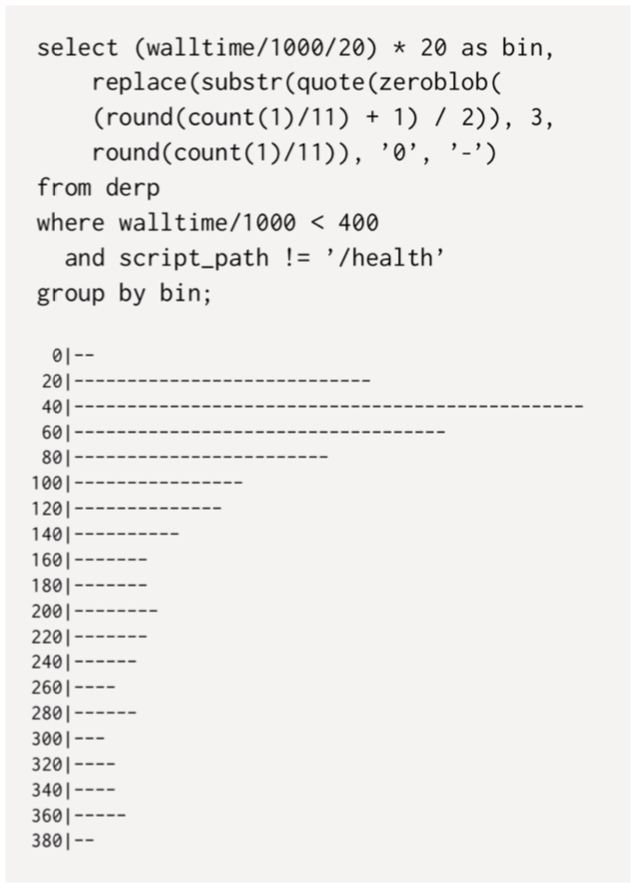

Time is also another critical factor: it is continuous and most networked applications operate on a cyclical basis, with peaks of activity here and there, like people do in their daily activities. This means that to compare performance across time, it is best to ensure that things are comparable, e..g, same time and day of the week for two consecutive measurements. This is close to the concept of “blocking” in experimental design. The next chapter on instrumentation or profiling is getting even closer to measurement (via activity logging and a metric that resumes to a database query) and laboratory experiments, although “(the) only way to test that theory is to collect measurements in production too”. Most importantly, what really matters is to store raw data (including metadata) in RAM, and not aggregated data or data with a lower time resolution. This will allow live interactive exploration and post hoc analysis when necessary. However, this means that we need a very fast database and an efficient search engine capable of operating on a very large dataset. From a practical viewpoint, this departs from classical SQL modeling since “(there) will be only one index, on the time dimension; we will rarely delete columns and never do joins.” Several examples of SQL queries for offline analytics are provided in chapter 6.

There is more to learn in the next chapters, especially if you are ready to perform all your statistical analysis in SQL, bearing in mind that

(with) sufficient stubbornness it is possible to wring insight out of nothing but a SQL prompt, but in this day and age no one should have to.

As a final word, here is a little gem from the very first pages of the book:

The age of a piece of code is the single greatest predictor of how long it will live.

To sum up, maybe the take away message could be something like: Log everything (as raw data), measure twice, iterate.

♪ The Kills • Ash & Ice