Permutation vs. bootstrap test of hypothesis

Here are short notes I took when reading articles or books about permutation and bootstrap test of hypothesis. I like the introduction given by Phillip Good(1) in his textbook (pp. 7–10).

Shortly after I received my doctorate in statistics, I decided that if I really wanted to help bench scientists apply statistics I ought to become a scientist myself. So I went back to school to learn physiology and aging in cells raised in petri dishes. I soon learned there was a great deal more to an experiment than the random assignment of subjects to treatments. In general, 90% of experimental effort was spent mastering various arcane laboratory techniques, another 9% in developing new techniques to span the gap between what had been done and what I really wanted to do, and a mere 1% on the experiment itself. But the moment of truth came finally–—it had to if I were to publish and not perish–—and I succeeded in cloning human diploid fibroblasts in eight culture dishes: Four of these dishes were filled with a conventional nutrient solution and four held an experimental “life-extending” solution to which vitamin E had been added. I waited three weeks with fingers crossed that there was no contamination of the cell cultures, but at the end of this test period three dishes of each type had survived. My technician and I transplanted the cells, let them grow for 24 hours in contact with a radioactive label, and then fixed and stained them before covering them with a photographic emulsion. Ten days passed and we were ready to examine the autoradiographs. Two years had elapsed since I first envisioned this experiment and now the results were in: I had the six numbers I needed. “I’ve lost the labels,” my technician said as she handed me the results. This was a dire situation. Without the labels, I had no way of knowing which cell cultures had been treated with vitamin E and which had not.

Then follows the general strategy of testing or decision making about statistical hypothesis:

- Analyze the problem—identify the hypothesis, the alternative hypotheses of interest, and the potential risks associated with a decision.

- Choose a test statistic.

- Compute the test statistic.

- Determine the frequency distribution of the test statistic under the hypothesis.

- Make a decision using this distribution as a guide.

It is interesting that this general strategy not only applies to permutation testing, but to bootstrap or parametric testing as well. Also, I like the fact that point 4 does not restrain the sampling distribution to be known under the “null” hypothesis, even if it is implicitly stated that the hypothesis under consideration is a null one. But as I pointed in another post, you may want to consider an alternative H0 which do not reflect the null effect.

The first part is mainly a summary of what is found on the Wikipedia section on Resampling. Resampling techniques include the bootstrap, jacknife, cross-validation and permutation procedures but they are not all equivalent with respect to their aims or computational requirements.

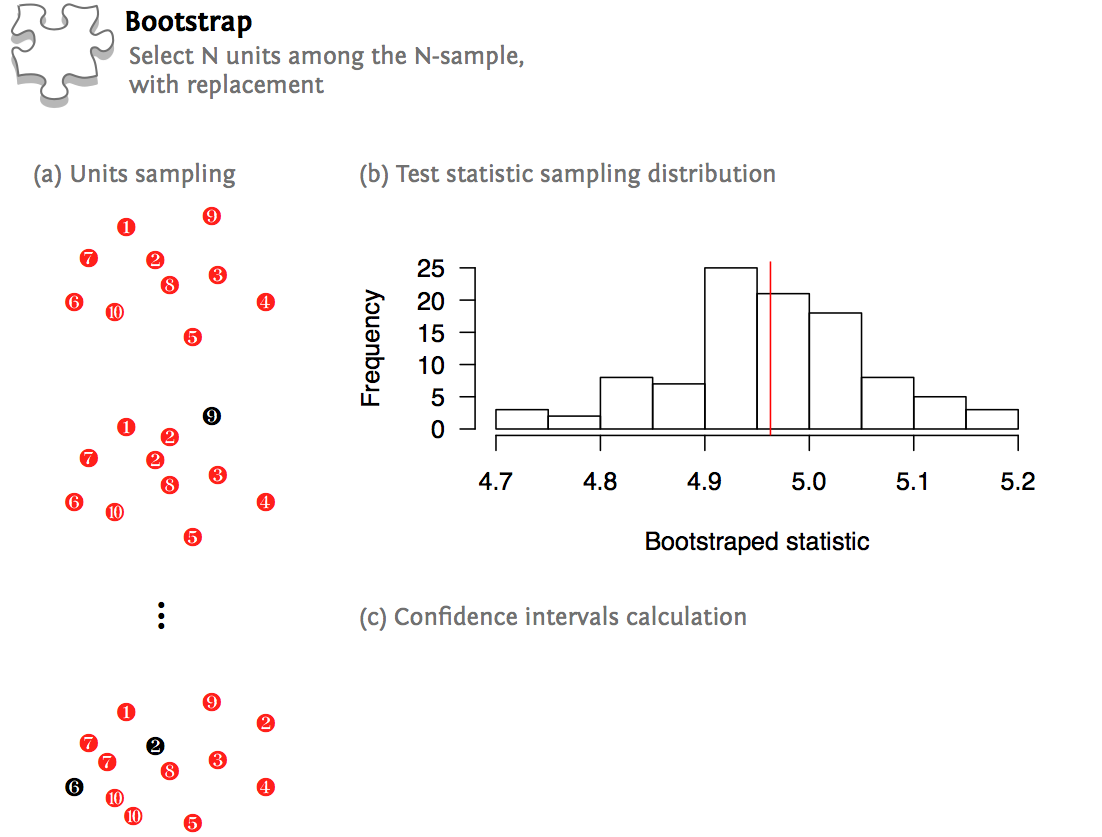

Bootstrap and jacknife techniques are mostly used for parameter estimation (sampling distribution under the null, bias and standard error of the test statistic, robust confidence intervals). Both methods estimate the variability of a statistic from the variability of that statistic between subsamples, rather than from parametric assumptions. Jacknifing might be easier to implement with complex design but bootstrap is now common practice in various field. For instance, I use it when I want to associate confidence intervals to Cronbach’s alpha, intraclass correlation, Spearman correlation or regression coefficients for small-sample studies.

Cross-validation is a general technique for estimating the predictive quality of a statistical model. Subsets of the data are held out for use as validating sets; a model is fit to the remaining data (a training set) and used to predict for the validation set. Averaging the quality of the predictions across the validation sets yields an overall measure of prediction accuracy. Various methods can be implemented for cross-validating a given model. Most of the time, these are: fold validation or leave-one-out scheme (which is just the extreme case of k-fold with k=1, and is equivalent to jacknife).

Finally, permutation or (re-)randomization tests are used for hypothesis testing, where the reference distribution is obtained by calculating all possible values of the test statistic, or a subset thereof, under rearrangements of the labels on the observed data points. In the former case, the test is said to be an exact test. When we only derive the empirical distribution for a fixed number of samples (say, 1000 to get an expected alpha level of 5%), this boils down to an approximate test.

The following picture summarizes the aforementioned procedures:

A simple bootstrap can be carried out in R with few lines of code, but we will see later on that the R boot package offers more convenient functions:

n <- 100

y <- rnorm(n, mean=5)

ym <- mean(y)

resample <- function(k, x) replicate(k, sample(x, k, replace=TRUE))

hist(apply(resample(n, y), 2, mean))

abline(v=ym, col="red")

For the cross-validation procedure (half-split), I used the following snippet:

n <- 100

beta <- 1.5

x <- rnorm(n)

y <- beta*x + rnorm(n)

idx.train <- seq(1, n, by=2)

idx.test <- seq(1, n)[-idx.train]

df <- data.frame(id=1:n, x=x, y=y)

beta.hat <- coef(lm0 <- lm(y~x, data=df, subset=id %in% idx.train))

y.pred <- beta.hat[1]+df$x[idx.test]*beta.hat[2]

with(df, plot(x, y, cex=.8, pch=19, las=1))

with(subset(df, id %in% idx.train), points(x, y, col="red", pch=19, cex=.8))

with(subset(df, id %in% idx.test), segments(x, y, x, y.pred))

abline(lm0)

legend("topleft", c("Train", "Test"), col=c(2,1), pch=19, bty="n")

I also fetched several articles about permutation strategy when dealing with more complex designs, especially those including covariates(2) or relying on split-plot arrangements(3). Many applications are found in omics or neuroimaging studies, see refs 4–6.

Here, I shall enumerate R packages that provide such functionnalities: permax, boot, coin, lmPerm, MPT.Corr, caret, glmperm

other packages I don’t tried yet: permutest {CORREP}

should point to other wikipedia entry, like “Cross-validation”, and StackExchange Q526

> Case in point: say that you have a true linear model with a fixed number of parameters. If you use k-fold cross-validation (with a given, fixed k), and let the number of observations go to infinity, k-fold cross validation will be asymptotically inconsistent for model selection, i.e., it will identify an incorrect model with probability greater than 0. This surprising result is due to Jun Shao, "Linear Model Selection by Cross-Validation", Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 486-494 (1993). (h/t @gappy)add and discuss the following reference: Molinaro et al. Prediction error estimation: a comparison of resampling methods. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) (2005) vol. 21 (15) pp. 3301-7

References

- Good, P. (2005). Permutation, Parametric, and Bootstrap Tests of Hypotheses (3rd ed.). Springer.

- Anderson, M.J. (2000). Permutation tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Canadian Journal of Fish and Aquatic Science, 58: 626–639.

- Legendre, P. and Legendre, L. (1998). Numerical Ecology (2nd ed.). Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Nichols, T.E. and Holmes, A.P. (2001). Nonparametric Permutation Tests For Functional Neuroimaging: A Primer with Examples. Human Brain Mapping, 15: 1–25.

- Ojala, M. and Garriga, G.C. (2010). Permutation Tests for Studying Classifier Performance. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 11: 1833–1863.

- Park, P.J., Manjourides, J., Bonetti, M., and Pagano, M. (2009). A permutation test for determining significance of clusters with applications to spatial and gene expression data. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(12): 4290–4300.