On getting into richer data structures

I spend most of my time programming in Python or Scheme these days. Here are some thoughts about Python after years of R for data scraping and wrangling.

I am not going to speak about high-level programming with classes and decorators or whatever, neither am I interested in the domain-specific versus generic language debate. John D. Cook gave an excellent talk on this years ago. Let’s face it: R is great for statistical computing when your data conforms or can be transformed to conform to the expected model, and few commercial packages offer as many statistical estimators and techniques for mining and visualizing multidimensional data. Sometimes a more general programming language, like Python or Scheme, may be more malleable, though.

Not that I am also not going to even mention that whoever think that significant indentation is a plus to the language is probably out of control or in a state of advanced dementia. See also this old post.

To be honest, I only made a modest usage of Python 2.x for teaching between 2010 and 2014 (and first one was before 2004), and I am not even a real programmer–I mean, I have never been paid to write computer programs, and IT has always been a tool rather than a reason for research. I would love to hear of a better tutorial than Peter Norvig’s one, Python for Lisp Programmers, even if I am neither a Lisp programmer. Anyway, in this post, I am rather interested in ordinary data structures that I find useful to process data in simple scripts, and I realize this may be just Python 101 for Python connoisseurs.

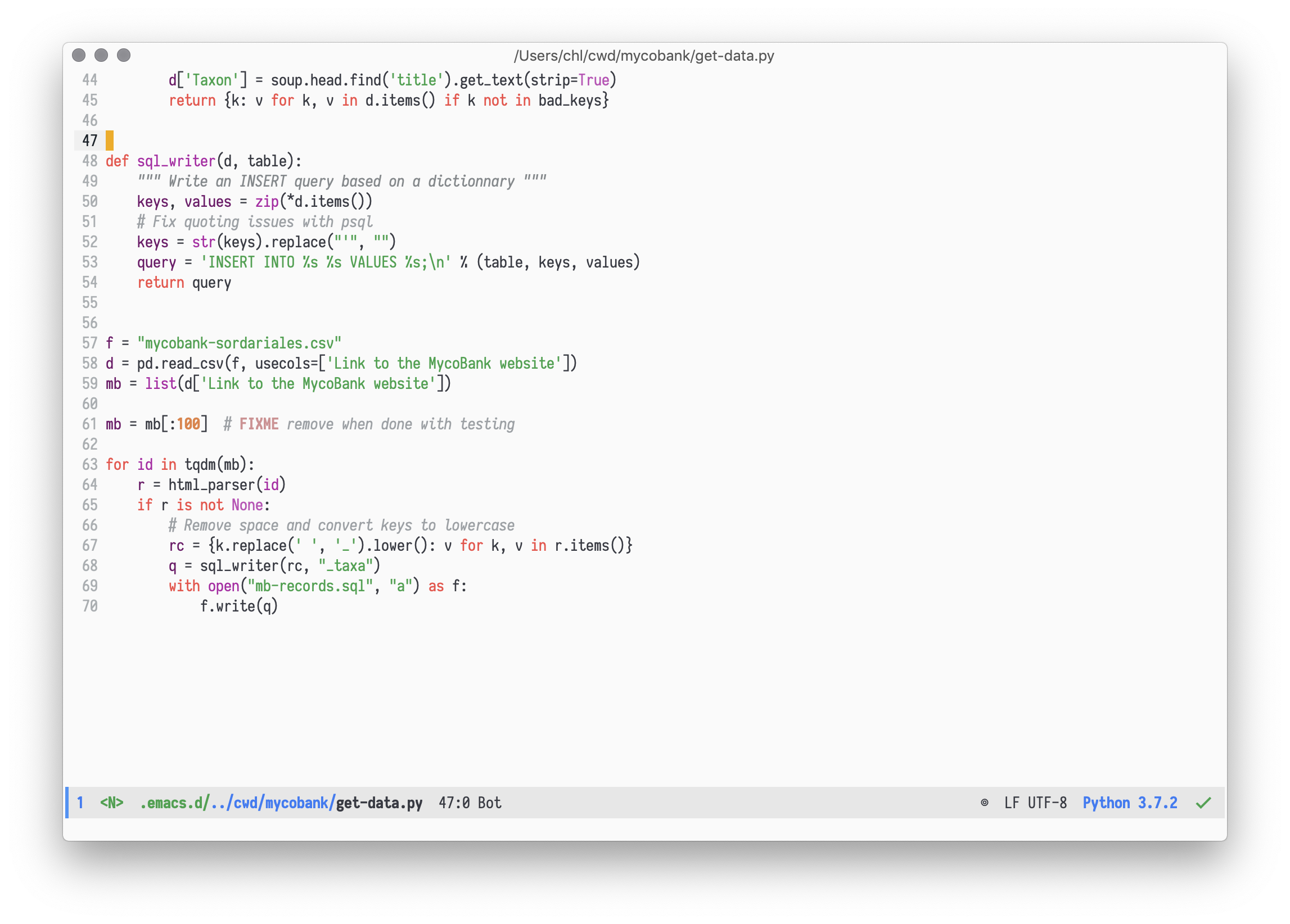

Surely, having richer data structures at hand offers new horizons. Being able to work with mutable (list and dict) or immutable (tuple) objects is a plus, even if I consume the latter due to side effects (e.g., zipping on a dict or a pair of lists). Dictionaries are really interesting data structures, however. While named vectors or lists have always been available in R, there is no comparison possible as no canned method is available to exploit this type of pairing (I once provided an illustration of what we would have to write in R to reproduce zip or enumerate), notwithstanding the fact that it would have relatively poor application given the omnipresence of data frames and named lists in R. Anyway, there seem to exist a few packages to mimic dictionaries or hash tables, but these are add-ons while, on the contrary, this is built-in in Clojure or Racket (including either mutable or immutable version in the latter case). Here is an example of my using a dict to create an SQL statement using a dict:

(The keys = str(keys).replace("'", "") instruction is here to ensure that column names are unquoted when they are sent to PostgreSQL.)

I still find a bit confusing that deleting an item from a dictionary or a list may be accomplished either using methods (.pop()) or what resemble functions but are in fact just keywords (del). Both approaches have the same computational complexity, but pop returns its item while del allows to use slice. I tend to think as pop (without push, though) the way Perl does, and more generally how stacks work, even if we can “pop” an element at any position.

List comprehensions and generators are probably the best functionality available in Python, compared to R or MATLAB/Octave (which I used to use for some years before R). Some math functions like sum are even capable of dealing with iterable objects derived from a generator expression (e.g., x*x for x in range(10), which is equivalent to map(lambda x: x*x, range(10)) if we were to rely on a lambda function). When iterating once or when lazy evaluation is of concern, generators prove to be very elegant. I believe that was one of the reasons for people’s enthusiasm with regard to Python 3 itself, after new packages like itertools.

I am not a big fan of the .format() option for strings (available since version 2.6 apparently) and I generally go the older way (%), which still works in Python 3. Maybe this is just because I only have very rudimentary use of printing statements, and I am pretty sure there are use cases where format is to be preferred. Hopefully, with Python 3 we no longer have to worry with encoding and decoding strings.

Note that I am really just processing data (reading and cleaning data from my local machine or from the internet, exporting data to PostgreSQL using pre-written INSERT statements, building reactive websites, or generating custom logs) in my daily job, often in conjunction with sed and the excellent GNU coreutils and I am not actually using Python in statistical computing, so I will save my comments on this aspect for another post. So far, so good. I didn’t get to half of what I wanted to write that I realize I have to go back to the documentation on some of the points I wanted to address. So, I guess, next in a future post probably…