Dose finding studies and cross-over trials

Here are some notes on cross-over trials and within-patient titration in indirect assays.

Most of my literature review started with Senn’s textbook, Statistical Issues in Drug Development (Wiley, 2007, pp. 317-336). Contrary to direct assays where we know what we want to achieve, say a given response to treatment, and we adjust the dose until this goal is reached, in indirect assays individual response is studied as a function of the dose and a ‘useful dose’ is decided upon afterwards. Studies on dose finding are generally done through between- or within-subject design. In within-patient design–dose escalation or cross-over–doses are given in ascending order, keeping in mind that within-patient titration share most of the problems of cross-over trials (see below), with additional limitations (dose and period effects are confounded) unless there’s a parallel placebo group or an intervening placebo treatment in the dose escalation sequence. In any case, there seems to be some agreement on the fact that within-patient designs (cross-over or dose escalation) usually perform better than any parallel-groups design.(1) However, the main difficulty with analyzing dose escalation studies is that it generally requires complex non-linear random-effects models which allow for drop-out to be used.

In cross-over trials, patients are randomly allocated to a sequence of treatments where treatments are interleaved with (active or passive) wash-out periods. Such a design is typical of a design where subject is taken as his own control and cross-over trials are an example of a Latin square design where treatments appear only once in each period and in each sequence. A simple design is the AB/BA cross-over where the two treatments under study are administered in both order: A then B, or B then A. Carry-over effects are of much concerns in this approach, and even if different weighting schemes have been proposed to eliminate or render them innocuous it seems that the best is actually to take into account pharmacokinetic and pharmacological theories when devising wash-out period. In the special case of single-dose studies the wash-out period has been proven to be effective in general.(5)

Some references are given in the References section, but here is one good textbook by Stephen Senn himself: Senn S. Cross-over trials in clinical research (2nd ed.), Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2002.

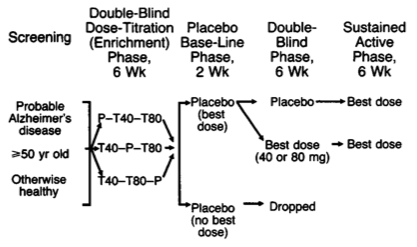

As has been suggested, a parallel-groups design can also be used in effective dose studies. Assuming 3 doses for the active group and a standard deviation of the outcome (e.g., pain score) of 45 points, with a minimal clinical important difference of 25 points, we would need 54 patients in each group to ensure 80% power. However, titration assays are often done in two-stage, with a first randomization of patients on dose sequence, and a second random allocation of patients to effective dose group or a placebo, see e.g. Davis (1992) and the following illustration.

Free combination therapy is another topic where complex designs might be required (factorial or response surface with quadratic terms added) but it is generally found in pre-clinical studies.(6,7) Of note, fixed-dose combinations have been shown to perform usually better than free-drug combination, especially in terms of adherence which was found to be reduced by 25% according to Bangalore and coll.(8)

References

- Sheiner LB, Hashimoto Y, and Beal SL. A simulation study comparing designs for dose-ranging. Statistics in Medicine. 1991; 10: 303–321.

- Senn, S. Cross-over trials in Statistics in Medicine: The first ‘25’ years. Statistics in Medicine. 2006; 25:3430-3442.

- Senn, S. The AB/BA Cross-over: How to perform the two- stage analysis if you can’t be persuaded that you shouldn’t. In Hansen, B and De Ridder, M. (eds.) Liber Amicorum Roel van Strik, Erasmus University, Rotterdam; 1996, pp. 93-100.

- Senn, S, Lillienthal, J, Patalano, F, and Till, D. An incomplete blocks cross-over in Asthma: A case study in collaboration. In Vollmar J and Hothorn, LA (eds). Biometrics in the pharmaceutical industry, vol. 7, Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fischer; 1997, pp. 3–26.

- D’Angelo G, Potvin D, and Turgeon J. Carryover effects in bioequivalence studies. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2001; 11: 27–36.

- Machado SG, Robinson GA. A direct, general approach based on isobolograms for assessing the joint action of drugs in pre-clinical experiments. Statistics in Medicine. 1994; 13:2289–2309.

- Straetemans, R, O’Brien, T, Wouters, L, Van Dun, J, Janicot, V, Bijnens, L, Burzykowski, T, Aerts, M. Design and Analysis of Drug Combination Experiments. Biometrical Journal. 2005; 47: 299-308.

- Bangalore S, Kamalakkannan G, Parkar S, Messerli FH. Fixed-Dose Combinations Improve Medication Compliance: A Meta-Analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007; 120:713–719.

- Davis, KL et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study of Tacrine for Alzheimer’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992; 327: 1253-1259.

- Dette, H, Bretz, F, Pepelyshev, A, and Pinheiro, JC. Optimal Designs for Dose Finding Studies. Journal of the American Statisical Association. 2008; 103: 1225-1237. See also the DoseFinding R package.