The Competitive Programmer's Handbook

I enjoyed reading the Competitive Programmer’s Handbook (available online in PDF format). Here is a brief review with additional comments.

The book is especially intended for students who want to learn algorithms and possibly participate in the International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) or in the International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC). Of course, the book is also suitable for anybody else interested in competitive programming.

Even if you are not interested in coding challenges, like is my case, you will probably learn a few tidbits from this book. As for myself, this was also a good opportunity to revisit Python 3.x. Unlike the Imposter handbook, this book makes heavy use of C (in fact, C++ 11) and it provides many guidance for algorithm design, especially to speed up things a bit. Recall that this is intended for people involved in programming contests where slow algorithms are not well rewarded, or not at all.

As Evan Miller once said in his essay on the Mathematical Hacker, closed-form formulae, like Binet’s formula $f(n) = \big[ (1+\sqrt{5})^n - (1-\sqrt{5})^n \big] / 2^n\sqrt{5}$ in the case of Fibonacci numbers,1 and more generally good mathematical skills are essential to writing efficient code. In the present book, Antti Laaksonen mentions Faulhaber’s formula, which allows to express the sum of the $p$-th powers of the first $n$ positive integers using closed-form formula. For example, it is well known that the sum of the $n$ first integers can be written as $\tfrac{n(n+1)}{2}$. How about the sum of the 7th powers, $1^7 + 2^7 + 3^7 + \dots$? There is more to see in Eric Weisstein’s article on Power Sum available on MathWorld, in particular the “double series approach” where it is shown that we can compute $S_p(n) = \sum_{k=1}^n k^p$ using the following expansion: $$ S_p(n) = \sum_{i=1}^p\sum_{j=0}^{i-1}(-1)^j(i-j)^p {n+p-i+1 \choose n-i} {p+1 \choose j}.$$ This yields the following polynomial in the case of the 7th powers: $\tfrac{1}{24}(3n^8 + 12n^7 + 14n^6 - 7n^4 + 2n^2)$, and a value of 412420800 for $n=15$.

def s(n):

return 1/24 * (3*n**8 + 12*n**7 + 14*n**6 - 7*n**4 + 2*n**2)

s(15)

Other than mathematical insights, well-crafted algorithms often comes to the rescue (if you know them of course) and might even allow to reduce a naive $\mathcal O(n^3)$ idea to a simple $\mathcal O(n)$ (i.e., only one for-loop) algorithm. This is the case of the Kadane’s algorithm. If you want both, go buy the TAOCP. It is really worth the bill!

The description of time complexity and some use cases (§2.2) is particularly well put. For instance, non-polynomial algorithms and their time complexity are described as follows:

- $\mathcal O(2^n)$ This time complexity often indicates that the algorithm iterates through all subsets of the input elements. For example, the subsets of {1,2,3} are $\varnothing$, {1}, {2}, {3}, {1,2}, {1,3}, {2,3} and {1,2,3}.

- $\mathcal O(n!)$ This time complexity often indicates that the algorithm iterates through all permutations of the input elements. For example, the permutations of {1,2,3} are (1,2,3), (1,3,2), (2,1,3), (2,3,1), (3,1,2) and (3,2,1).

Combinations, permutations and sequence generators are important in statistical computing, so it is always a good idea to know where to find good algorithms. It turns out that the author uses C++ and that there is already an implementation of permutation using lexicographic ordering in the STL (std::next_permutation). The author discusses the use of permutations later in §5.2. As of Python we could rely on the itertools module. It is quite easy to get started, notwithstanding the fact that there are great tutorials on itertools. Or, we can write a custom function, using one of the algorithms proposed by Don Knuth, which will probably saves some time compared to the above generator. One could also rely on SymPy Permutation (see also multiset_partitions from the utilities.iterables modules) or even make use of coroutines.

Sorting is another common pattern in computer science. Finding duplicated entries or the most frequent item in a list usually requires that data be sorted first. Again, many algorithms are available in the TAOCP. Here, the author describes the bubble sort algorithm ($\mathcal O(n^2)$), merge sort ($\mathcal O(n\log n)$) and counting sort ($\mathcal O(n)$). The bubble sort can be written as follows in C:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < n-1; j++) {

if (array[j] > array[j+1]) {

swap(array[j],array[j+1]);

}

}

}

Given how easy it is to swap two elements in Python, the translation is straightforward. Note that Python has facilities to sort items in a list (in-place) or an iterable via the Timsort algorithm, which is stable, while C++ STL provides std::sort, which is not. As the author notes, “it is almost never a good idea to use a home-made sorting algorithm in a contest, because there are good implementations available in programming languages.” The same applies to pseudo random number generator: it is generally not a good idea to implement one from scratch, but you can provide your own implementation. There is also a specific discussion with implementation details of searching and finding minimum or maximum elements in a list.

The next chapter is about data structures (dynamic arrays, sets, maps and iterators) and it is very specific of C++ so I will skip it. Chapters 5 and 6 are about general strategies to solve a given problem. This covers complete search (i.e., generating all solutions using brute force) and backtracking with or without pruning, and then greedy algorithm and dynamic programming. The latter two approaches are illustrated on a similar problem: let’s say we have a set of coins and we need to form a sum of money $n$ using those coins; what is the minimum of coins needed? E.g., with the set {1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200} and an objective value of 520, the optimal solution is to select coins 200+200+100+20. Other approaches requiring specialized data structures close this first part of the book. I will be skipping Part II which deals with graph theory and jump to Part III directly.

The third and last part of the book covers so-called “advanced topics”. This includes number theory, combinatorics, game theory, among others. Prime numbers are important in number theory and cryptography, and thus it appears natural to master basic algorithm to enumerate prime numbers (e.g., using a sieve) or test whether a number is prime or even a perfect number (a perfect number $n$ is equals to the sum of its factors between 1 and $n$ − 1). As an example, the following function allows to test whether a number is prime by considering all values between 2 and $\lfloor\sqrt{n}\rfloor$. Again, it is easy to translate this C code to Python:

bool prime(int n) {

if (n < 2) return false;

for (int x = 2; x*x <= n; x++) {

if (n%x == 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

Prime factorization and modular arithmetic are other important concepts to master when dealing with integers. One must keep in mind that unsigned integers are represented modulo $2^k$ (where $k$ is the number of bits of the data type, typically 32) on a computer so that 123456789 times 123456789 becomes 2537071545 (1234567892 mod 232) in C (the maximum value for a variable of type long, defined as LONG_MAX, is 2147483647), while Python has no real problem to work with large integers since there is no explicit defined limit other than sys.maxsize. Anyway, if you are looking for some data visualization challenge, you can try to implement the Ulam spiral or verify that there is no prime numbers in Pascal’s triangle other than ${n \choose 1}$ and ${n \choose n-1}$.

Regarding combinatorics, the author uses the “boxes and balls” model with nice pictures to illustrate different scenarios, namely, “each box can contain at most one ball”, “a box can contain multiple balls”, or “each box may contain at most one ball, and in addition, no two adjacent boxes may both contain a ball”. In the latter case, assuming $k$ balls are already put in $n$ boxes with at least an empty box between each two adjacent boxes, there are ${n-k+1 \choose n-2k+1}$ ways to choose the positions for the remaining empty boxes. Also Catalan number are presented as the number of valid parenthesis expressions that consist of $n$ left parentheses and $n$ right parentheses, an appreciable property for any serious Lisp user! For instance, $C_3 = 5$ and we have the following solutions: ()()(), (())(), ()(()), ((())), (()()), which are all valid Lisp constructions. One of the formula used to compute Catalan numbers involves binomial coefficients:

$$ C_n = \frac{1}{n+1}{2n \choose n}. $$

This in fact follows from the fact that there are ${2n \choose n}$ ways to arrange $n$ left and right parenthesis, of which ${2n \choose n+1}$ are invalid expressions, so that ${2n \choose n} - {2n \choose n+1} = {2n \choose n} - \frac{n}{n+1}{2n \choose n} = \frac{1}{n+1}{2n \choose n}$. Again, the author explains this as clearly as in the case of C++ tricks or algorithm design. Note that the above expression can also be written as $\prod_{k=2}^n \frac{n+k}{k}$, which is obviously easier to implement in C or Python (and probably better than a recursive solution or using binomial coefficients):

def cn(n):

val = 1

for k in range(2, n+1):

val = val * (n+k)/k

return val

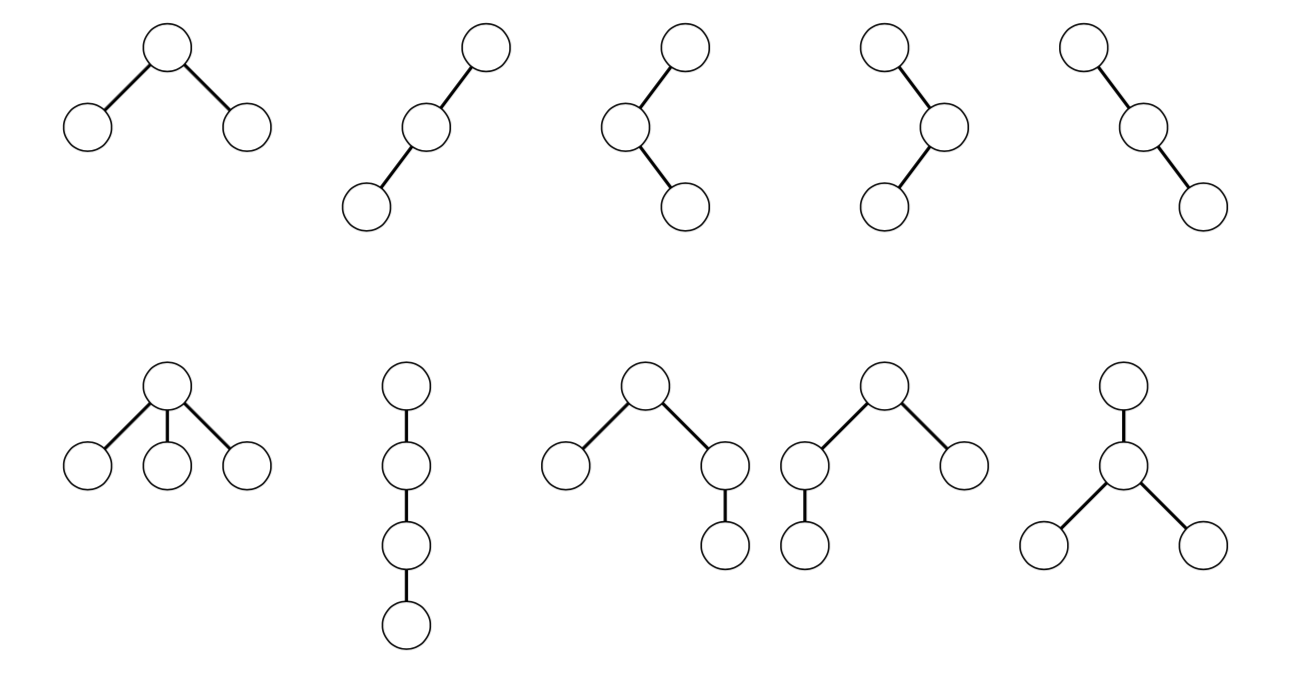

A related problem is the Catalan’s Triangle. Finally, Catalan numbers are also related to binary (top) and rooted (bottom) trees (see below), and many other data structures (PDF).

If you are interested in competitive programming, you may also want to take a look at some of the references cited in the book:

- S. S. Skiena and M. A. Revilla: Programming Challenges: The Programming Contest Training Manual, Springer, 2003.

- S. Halim and F. Halim: Competitive Programming 3: The New Lower Bound of Programming Contests, 2013.

- K. Diks et al.: Looking for a Challenge? The Ultimate Problem Set from the University of Warsaw Programming Competitions, 2012.

Other than that, I think this is a great book for learning data structures and basic algorithms, and despite the title it provides a clear and principled approach to computer science using C++. Of note, you may also like these C & C++ programming notes written by Ben Langmead.

♪ Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds • Push the Sky Away

Other approaches are discussed in So How Do You Actually Calculate The Fibonacci Numbers? ↩︎