Motzkin numbers

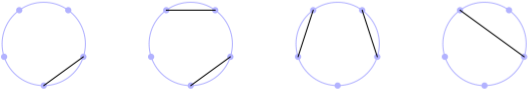

In one of my last post, I discussed de Bruijn graph based on one of Rosalind problems in the Bioinformatics track. This post is again about graphs, and Rosalind problems. The Motzkin number Mn represents the number of ways to form a noncrossing matching (i.e., non-intersecting chords) in the complete graph Kn with n nodes. A related quantity is the Catalan number Cn which counts the number of ways to form a perfect noncrossing matching; in this case the matching includes every node in the graph, which must necessarily contain an even total number of nodes. A picture is better than thousand of words, so I wrote a bit of Metapost (long time no see!) to reproduce part of the figure for M5 available on Wikipedia:

The following recurrence relation can be used to find the value of Mn, for any n:

$$ M_n = M_{n-1} + \sum_{k=2}^n M_{k-2}\cdot M_{n-k}, $$

with $M_0=M_1=1$.

Given an RNA sequence s, the number of noncrossing matchings of basepair edges in the bonding graph of s corresponds to the number of possible secondary structures for that RNA string. It means that the recurrence relation shown above must accomodate the following base pairing rule: A $\leftrightarrow$ U and C $\leftrightarrow$ G.

Here is my solution, which only exploits Biopython facilities to read the input file, which is in Fasta format:

def motz(seq):

if len(seq) <= 1:

return 1

if seq in matches:

return matches[seq]

else:

matches[seq] = motz(seq[1:])

for i in range(1, len(seq)):

if seq[i] == codons[seq[0]]:

matches[seq] += motz(seq[1:i]) * motz(seq[i+1:])

return matches[seq]

rna = SeqIO.read("motz.txt", "fasta")

codons = {"A": "U", "U": "A", "C": "G", "G": "C"}

matches = {}

print(motz(str(rna.seq)) % 1000000)

Note that the task is to give the results modulo 1000000, hence the modulo operator in the print instruction.

So basically, this is sort of “dynamic programming”, which amounts to break the problem into smaller problems and use the solutions of the subproblems to construct the solution of the larger one. Since this may yield to a very large number of similar subproblems that we need to solve again and again — hence increasing the overall running time — dynamic programming can be thought of as a way to avoid recomputing values that were already computed in a previous step.1 A well-known approach to this approach is memoization.

In this particular case, we use a global dictionary to store the succesive matches we found when reading the string, after taking into account base pairing. If the value was already computed, just return it (this is the second if statement); otherwise, compute the current value, add it to the dictionary, and return it. Then, we just have to reduce the problem to noncrossing matchings, and to select the next starting character in the string.

Let’s see it in action for a toy example: (I just added a print statement at the top of the motz function to display intermediate results.)

In [5]: s = "AUAU"

In [6]: motz(s)

{'AU': 2, 'UAU': 3, 'AUAU': 7, 'UA': 2}

Out[6]: 7

Jones, Neil C. & Pevzner, Pavel A. An Introduction to Bioinformatics Algorithms. The MIT Press, 2004. ↩︎